Nipah Virus Transmission via Date Palm Sap: Why The Next Pandemic Could Be Sweet

It is 4:00 AM in the Manikganj District of Bangladesh. The winter mist hangs heavy over the village, creating a ghostly veil. A 12-year-old boy climbs a notched tree trunk to retrieve a clay pot filled with khejur rash—raw date palm sap. He pours a glass for himself, unaware that he is about to trigger a deadly chain of events.

Two weeks later, the boy is fighting for his life with severe brain inflammation. He isn’t a victim of a lab leak. He is a victim of a specific, ecological mechanism: Nipah virus transmission via date palm sap. While the world worries about airborne super-flus, one of nature’s deadliest pathogens is exploiting a simple harvest tradition to jump from bats to humans.

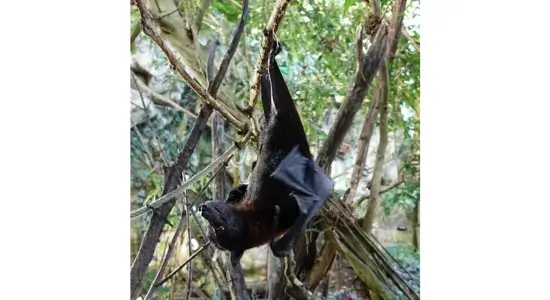

The Flying Fox and the “Cocktail” Effect

To understand the mechanics of Nipah virus transmission via date palm sap, you first have to meet the host. The Pteropus bat, or Flying Fox, is a reservoir for the virus. These bats are immune super-carriers, capable of harboring high viral loads without getting sick.

The problem arises from a shared appetite. In rural Bangladesh, humans tap date palm trees for their sugary sap. Unfortunately, Pteropus bats love this sap too. Infrared cameras have captured bats licking the sap flow and, crucially, urinating into the collection pots.

When locals drink this raw sap the next morning, they are ingesting a direct dose of the virus. This unique route of Nipah virus transmission bypasses the need for an intermediate animal host (like pigs, which were the vector in Malaysia), making the date palm sap pathway a uniquely dangerous ecological trap.

Why This Transmission Route is So Deadly

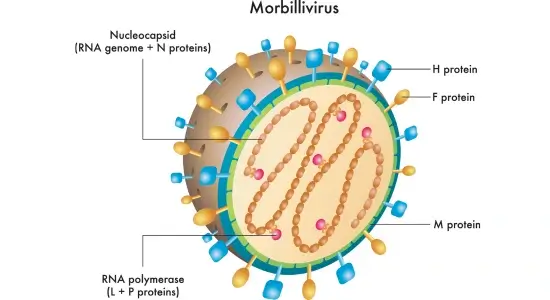

You might remember the movie Contagion. The fictional virus MEV-1 was modeled on Nipah for a reason. Nipah is a paramyxovirus that attacks the brain, causing encephalitis with a fatality rate between 40% and 75%.

In the context of transmission via date palm sap, the risk is amplified because the virus is ingested in a liquid medium that protects it. Once inside, it binds to Ephrin-B2 receptors in blood vessels and nerve cells. If Nipah were as contagious as the flu, civilization would be in trouble. Currently, the “R0” (reproduction number) is low, but every time a spillover event occurs through contaminated sap, the virus gets another chance to mutate and adapt to human hosts.

The Long Shadow: Relapsing Encephalitis

Survivors of Nipah virus transmission aren’t always in the clear. The virus is known for the “Lazarus Effect” or Relapsing Encephalitis. It can hide dormant in the brainstem, protected by the blood-brain barrier, only to reactivate months or years later. This makes preventing the initial infection—by stopping the consumption of raw, contaminated sap—even more critical.

The Takeaway

The story of Nipah virus transmission via date palm sap teaches us that pandemics aren’t just biological accidents; they are often ecological consequences. As we encroach on bat habitats, we force them to feed closer to us.

The solution is deceptively simple: Bamboo skirts can be placed over the sap pots to keep bats out, or the sap can be boiled to kill the virus. But until these practices become universal, that sweet morning drink remains a game of Russian Roulette.

ref : WHO