While we often perceive ourselves as living in a rational and enlightened era, our attitudes toward death reveal lingering superstitions and anxieties. Even in contemporary society, we observe traditions such as avoiding negative comments about the deceased and attributing a continued presence to departed loved ones.

However, the beliefs and practices of our ancestors surrounding death far surpass our modern sensibilities in their intensity and peculiarity. For them, death was not merely a period of mourning but a time for elaborate rituals aimed at safeguarding the living from potential harm, often attributed to the deceased.

Consequently, ancient burial practices served a dual purpose: honoring the departed and protecting the community. Here are four examples of such outlandish practices.

Ancient Egypt: An Afterlife of Labor

Ancient Egyptian culture placed an extraordinary emphasis on the afterlife, viewing it as a continuation of earthly existence. This perspective shaped their elaborate burial customs, particularly for pharaohs.

The pharaoh’s luxurious afterlife was thought to require the continued service of their loyal attendants. Therefore, it was considered expedient to ensure their presence in the afterlife by including them in the pharaoh’s burial.

Ellen Morris, Professor of Ancient Studies at Columbia University, noted in 2007: “[The] tradition, so far as we can ascertain, began with the funeral of the very first king of the First Dynasty, Hor-aha. To honor and accompany this founding father of the unified kingdom, thirty-five people were slain at his tomb and twelve more were laid to rest around the three funerary enclosures that date to his reign.”

While such practices may seem cruel and megalomaniacal by modern standards, it’s possible that they were perceived differently in ancient Egypt. The ritual sacrifice may have been presented as a means of guaranteeing access to a comfortable afterlife, serving a king considered a god, thus avoiding potential hardship under a new ruler.

Nevertheless, the scale of these sacrifices is a sensitive topic for Egyptologists. As Egyptologist Emily Teeter told the New York Times in 2004, it is “embarrassing for Egyptologists” who usually “like to stress how relatively humane the ancient Egyptians were.”

Sagalassos, Turkey: Fear of the Restless Dead

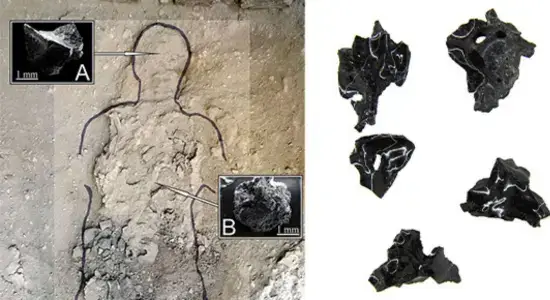

A unique burial discovered in the eastern necropolis of Sagalassos in southwestern Turkey in 2023 suggests a profound fear of the deceased’s return. The individual, buried between 25 BCE and 100 CE, was subjected to a series of unusual practices.

The body had been cremated, but the remains were left in place rather than moved to a secondary burial site. The grave was surrounded by intentionally bent nails, and the burial site was sealed with a covering of brick and lime.

While each of these practices had precedents, their combination was highly atypical.

The researchers who made the discovery explained: “Following cremation, we observe a series of atypical interventions. The deposition of nails appears to form a magical barrier surrounding the remains of the funeral pyre. The conversion of the pyre site in the burial place, and the use of a brick/lime covering are also unique among the funerary practices at Sagalassos.”

These practices strongly suggest an effort to prevent the deceased from escaping the grave. The bent nails were likely intended to “pin the spirits of the restless dead (so-called revenants) to their final resting place, so that they could not return from the afterlife,” while the heavy covering of brick and lime aimed to contain and possibly “disinfect” any malevolent forces.

The overall burial strongly indicates a fear of the restless dead, regardless of whether the cause of death was traumatic, mysterious, or potentially the result of a contagious illness or punishment. The living were clearly fearful of the deceased’s return.

Britain and Ireland: Burial at a Crossroads

British and Irish traditions offered another approach to dealing with the restless dead: disorientation. The deceased were often carried to their graves along designated “corpse roads” to prevent their spirits from finding their way back. For those deemed particularly dangerous, such as suicides, burial at a crossroads was employed.

Paul Devereux explained in his 2007 book Spirit Roads: An Exploration of Otherworldly Routes: “The corpses of suicides were buried at crossroads, for example. Suicide was considered a grave sin and social taboo, so those who died by their own hand would be outcasts even after death; a church burial was out of the question, while crossroads had the added benefit that ‘their spirits would be ‘bound’ there.” Gallows were often erected at crossroads for similar reasons.

This practice dates back to Anglo-Saxon times and persisted until an Act of Parliament in the 1820s led to its decline. References to this custom can be found in Shakespearean works. As Bill Angus and Lisa Hopkins explain in their 2020 book Reading the Road: From Shakespeare’s Crossways to Bunyan’s Highways, when Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream mentions restless spirits “in cross-ways have burial,” Shakespeare is “referencing a history of crossroads as places whose function was to arrest the movement of unquiet spirits, of suicides, executed murderers and traitors, who might otherwise walk the roads of the night home to the scenes of their particular traumas.”

“Here at the crossroads they may be fixed, sometimes literally staked, their movement arrested, paradoxically, in a place of permanent transit and transition.”

Poland: Anti-Vampire Measures

While Transylvania is often associated with vampires, archaeological evidence suggests that Poland may have its own claim to the myth’s origins.

Excavations at Pień, a village in southeastern Poland, have uncovered multiple “vampire” burials. These include a woman buried with a padlock on her big toe and a sickle across her neck, and a child similarly padlocked and buried face-down.

Dariusz Poliński, a professor of archaeology at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland: “All the features here indicate that this was a graveyard for the excluded, for those who should be forgotten.”

He explained that social status was irrelevant; anyone feared or ostracized was treated similarly in death.

These practices, though superstitious, were rooted in a grim pragmatism. Lesley Gregoricka, a bioarchaeologist at the University of South Alabama, explained to NPR in 2014 that placing a sickle across the neck was intended to prevent a potential vampire from rising and attacking the living.

Recent discoveries further illustrate this fear. In 2015, five more vampire burials were found in Drawsko, northwestern Poland, including a woman with a sickle across her pelvis, a rock on her neck, and a coin in her mouth. More recently, in Chełm, eastern Poland, archaeologists uncovered the remains of two children buried face down with their heads removed and separated from their bodies, and heavy stones placed on their torsos.

The Provincial Office for the Protection of Monuments in Lublin described these features as “characteristics of an anti-vampire burial,” noting that “burial with the face to the ground, cutting off the head, or pressing the body with a stone or stones are some of the burial methods used to prevent a person considered a demonic being from leaving the grave.”

The prevalence of such burials in Poland may be linked to explanations for misfortune and disease. Accusations of vampirism often arose after unexplained events, with the deceased becoming scapegoats for outbreaks or other calamities.

While grisly, these practices may be considered less violent than other methods of dealing with perceived threats from the dead. As Christopher Caes, a lecturer in Polish at Columbia University, observed to Smithsonian Magazine in 2017, “Vampirism in a sense is kind of humane, because the vampire is already dead. You don’t have to burn anyone at the stake, you don’t have to execute anyone, you don’t have to lock somebody up. You simply blame it on the dead.”

These examples reveal the diverse and often unsettling ways in which ancient cultures confronted death. While we may find these practices strange or barbaric, they offer insights into the anxieties and beliefs that shaped societies and their rituals.

Did this article spark your curiosity? Fact Fun delivers a daily dose of fascinating facts, covering everything from history and science to the downright bizarre! For a constant stream of awesome content, make sure to add us to your bookmarks!