Christmas, 1916. In Vienna, a young woman sat down to write a holiday card. Her hand hovered over the paper, pen poised. Minutes passed. Then hours. She didn’t blink. She didn’t speak. She didn’t move. She had not had a stroke, nor was she dead. She had simply… stopped.

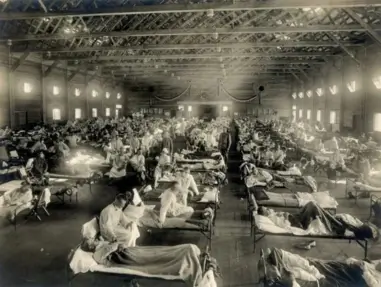

She was one of the first victims of a terrifying shadow plague that would sweep the globe alongside the Spanish Flu, claiming nearly a million lives and leaving millions more trapped in a living purgatory.

It was called Encephalitis Lethargica, or the “Sleepy Sickness.” It turned vibrant, healthy people into frozen statues, locking them inside their own bodies for decades. And then, just as mysteriously as it arrived, it vanished into the mist of history, leaving modern science with a chilling question: Where did it go, and when will it return?

The Nightmare of the “Living Dead”

The epidemic began quietly in Europe during the chaos of World War I. At first, doctors dismissed it as a reaction to mustard gas or a strange variant of influenza. But the symptoms were uniquely horrifying. Patients would start with a sore throat and fever, followed by double vision. Then, the “lethargy” set in.

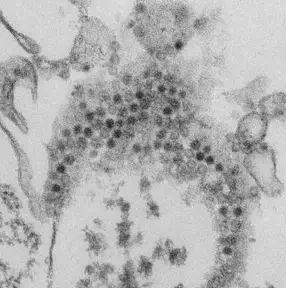

Enteroviruses have also been suggested as a possible cause of EL.

Enteroviruses have also been suggested as a possible cause of EL.

Source: CDC/Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Yiting Zhang

This wasn’t just tiredness. It was a pathological drowsiness so deep that patients could fall asleep while eating, walking, or speaking. Some drifted into a coma and never woke up (mortality rates hit 40%). But the cruelest fate was reserved for the survivors.

As the acute phase passed, thousands of victims didn’t recover. Instead, they entered a state of “post-encephalitic parkinsonism.” They became motionless, speechless, and expressionless. They were fully conscious—able to hear, feel, and think—but they lacked the “will” to move. They were ghosts haunting their own flesh.

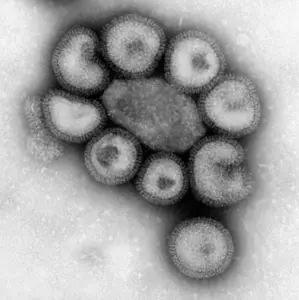

Influenza has been studied as one of the possible causes of EL.

Influenza has been studied as one of the possible causes of EL.

Source: Pixnio/F.A. Murphy

The 40-Year Coma and the Brief Awakening

For decades, these “living statues” were warehoused in institutions, forgotten by a world that had moved on. They remained frozen in time, aging physically but mentally trapped in the 1920s.

Then, in 1969, a miracle occurred. The neurologist Dr. Oliver Sacks administered a new experimental drug called L-DOPA (a precursor to dopamine) to these patients. The results were instantaneous and explosive.

Patients who hadn’t moved since the Hoover administration suddenly stood up, danced, sang, and spoke. They woke up to a world of television, jet planes, and rock and roll—a world completely alien to the reality they last remembered. It was a euphoric “summer of awakening.” But the tragedy wasn’t over. The brain damage caused by the disease was too deep. The drug’s effects became unstable, leading to violent tics and paranoia. Eventually, the L-DOPA stopped working. One by one, the awakened survivors drifted back into their statuesque slumber, this time knowing exactly what they were losing.

The Vanishing Act: Where is the Virus Now?

By 1927, the epidemic ended as abruptly as a switch being flipped. New cases simply stopped appearing. To this day, virologists have never definitively identified the pathogen. Was it a rogue strain of influenza? An autoimmune reaction to strep throat? An environmental toxin?

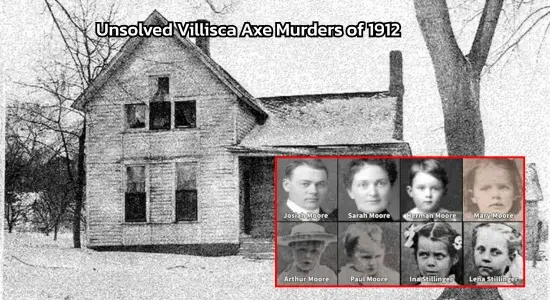

During The 1920s And ’30s, The ‘Sleeping Sickness’ Perplexed Doctors Around The World

During The 1920s And ’30s, The ‘Sleeping Sickness’ Perplexed Doctors Around The World

We don’t know. The virus didn’t just kill 500,000 people; it committed the perfect crime and left no fingerprints. But in recent years, isolated cases with similar symptoms have popped up globally, a grim reminder that Encephalitis Lethargica might not be extinct—it might just be sleeping, waiting for the right conditions to wake up again.

Conclusion

Encephalitis Lethargica remains the greatest medical mystery of the 20th century. It showed us that a virus can do something far worse than kill you—it can steal your time. For the survivors, life became a pause button that was pressed for forty years. As modern medicine advances, we can only hope that if this “sleeping sickness” ever wakes up, we will finally have the cure that the lost generation of 1916 never received.

ref : Oxford Academic (Journal Brain) , AMS